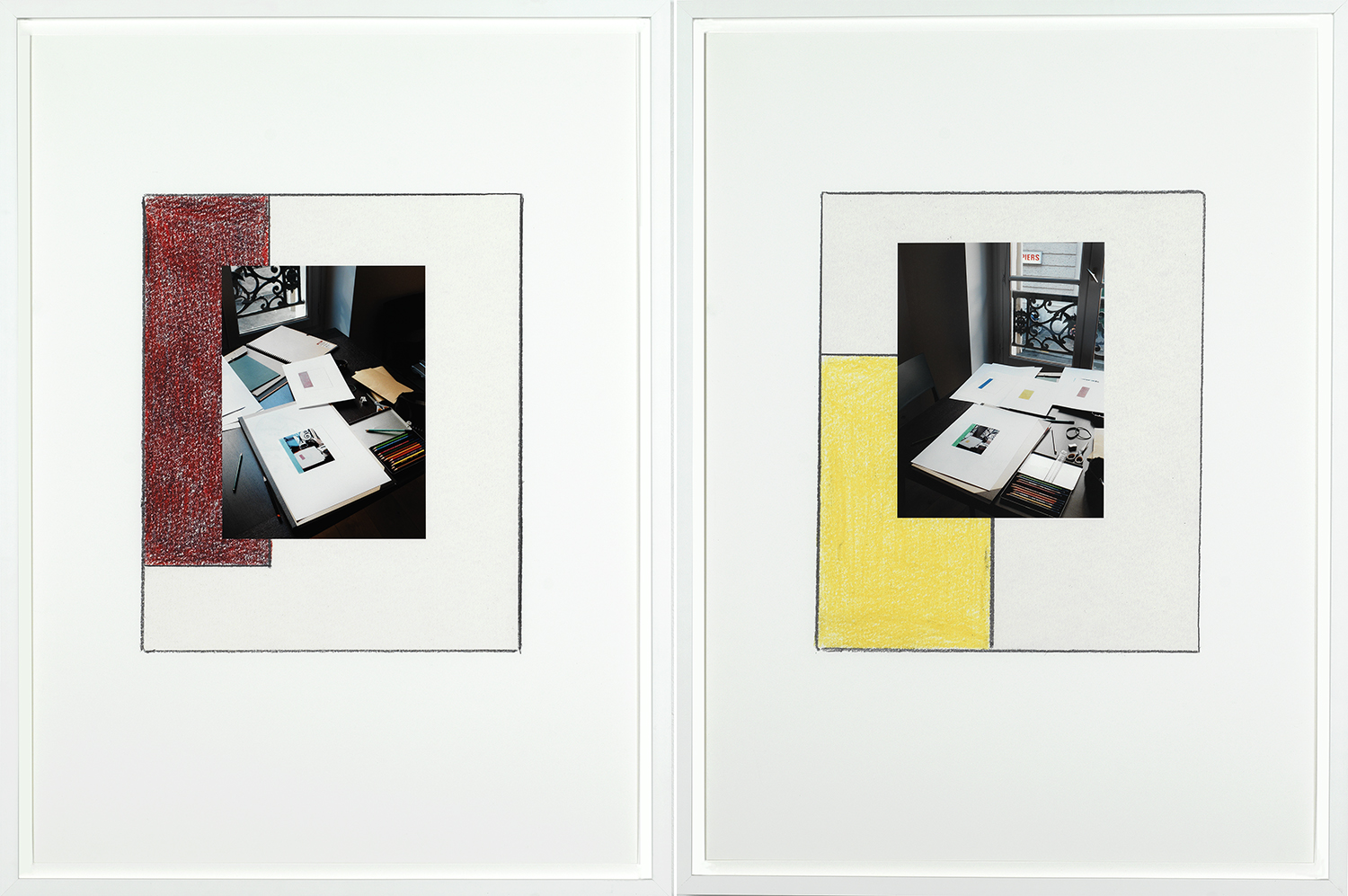

Enlarged Inkjet Study for Rue du Jour, Paris (Left, with black; right with blue), 2010

A drum kit sits on one wall of Ian Wallace’s Vancouver studio. Sun spills through high windows, plants tilting their leaves toward it. A worn leather couch and chairs create a seating area, while in the middle of the room, a large table dominates the space. Shelves upon shelves are filled with books and catalogues, records, cards, and other ephemera. Art is stored in another room across the hall along with yet more books. A select few pieces hang on the walls. It’s cozy, for an industrial building.

The lease is actually held by Emily Carr, Ian Wallace tells me. It’s a 30-year-old legacy that stems from a number of faculty and artists helping to maintain the lease rather than incur fines for breaking it. The space is still rented by some of those same artists.

Wallace grew up in West Vancouver. “[I] thought of myself as an artist from the very beginning,” he says. “I always had this idea of myself; I loved to draw. It was one of the few ways I could impress my friends because I wasn’t very good at sports.”

While he didn’t take a great many art classes, Wallace recalls going over to the old art school in town to take some night classes, though “nothing very serious.” In university, he became more serious. “I started to study in literature — poetry, comparative literature — then switched into art history because it was such a broader, more interesting, and richer field for me.” During his studies, Wallace was establishing his artistic practice as well.

[I] thought of myself as an artist from the very beginning. I always had this idea of myself; I loved to draw. It was one of the few ways I could impress my friends because I wasn’t very good at sports.

By 1967, before he even completed his master’s — a thesis on Piet Mondrian’s shift from landscape to abstract painting which he completed in 1968 — Wallace was on faculty at UBC, teaching art history. While getting such a position might seem out of reach for many students today, Wallace says, “I was pretty active as an artist, doing talks, writing art criticism for the Sun and the Province, and writing reviews for Canadian Art Magazine or Arts Canada as it was called then. I was totally active as a student. I had my name out there even though I was still a student. It was a survival technique.”

Throughout the 60s, Wallace experimented with reductive, minimalist, and conceptual styles. He still folds them into his work, particularly with monochrome drawings. “Within a frame, what’s your gesture going to be?” he asks. “I reduced it down to a coloured area that occupies a particular space in the picture. I fold it into a whole referencing system based upon photography.”

Photography plays a huge role in Wallace’s art and teaching career. Among his earliest students were Jeff Wall, Christos Dikeakos, and Rodney Graham, known now for their photography and photo-conceptual art. “I also established discourse around photo-conceptualism and the use of photography in conceptual art and their connection to each other to talk about the world,” he says. That conversation continued through the 70s; in the early 80s, Wallace, some of his students, and other local artists established what’s known as the Vancouver School or photo-conceptualism.

I was pretty active as an artist, doing talks, writing art criticism for the Sun and the Province, and writing reviews for Canadian Art Magazine or Arts Canada as it was called then. I was totally active as a student. I had my name out there even though I was still a student. It was a survival technique.

When photography first emerged as a technology, it wasn’t considered an artform. It was most popular as portraiture for the rising bourgeois class in the 19th century, Wallace explains. Portraits were seen as a way to record the family’s existence, just as, previously, painted portraits recorded their existence. Painting, of course, was very expensive and not accessible to most families.

Wallace discusses the emergence of photography among the bourgeois, and later aristocrats, in his academic writing. “Painting, as a practice, is already assumed to be art,” says Wallace. “But photography isn’t necessarily art because it also supplies information, rather than the more specific idealizations about meaning that comes out of the rubric of what we understand to be art.” In other words, because photography emerged as a visual form to relay information rather than a form of creative expression, it wasn’t considered art. Over decades, that assumption, of course has evolved – in part with the help of artists like Wallace.

Wallace has always been interested in the intersection of painting and photography. In the 70s, using hand-coloured photographs, he created large photo murals, up to 70 feet long. It wasn’t until the 80s that technology allowed Wallace to make an even bigger leap.

“In the early 80s, I did this Poverty Series that involved photography – photographs taken from film stills, which I had also done earlier in the 70s – silk-screened onto canvas,” he tells me. By 1985, printing technology had evolved so that you could print large-scale colour photos and laminate them onto other surfaces.

Expo 86 saw an injection of funding and technology come to Vancouver. It was a chance for Vancouver to evolve. In order to print the large-scale campaign images promoting the Expo, printers started to install bigger and better printing presses. “For Expo 86, Colorific up the street bought the first really expensive photo lamination machine, which was a great big press that, through heat and pressure, pressed the photograph and laminated it onto aluminum and foam core.”

For Expo 86, Colorific up the street bought the first really expensive photo lamination machine, which was a great big press that, through heat and pressure, pressed the photograph and laminated it onto aluminum and foam core.

Wallace’s immediate reaction? To test laminating his photos directly onto canvas. Overnight, he’d gone from trying to glue his photos (rather unsuccessfully, he admits) to canvas, to laminating them. “Since then, I’ve been working with this discourse of mapping a photograph onto a field of canvas, which brings up discourses about painting, about abstraction, about composition, about formalist discourses in painting, but also the social content of photography, and all the themes you could evolve from that.”

By this time, Wallace had settled on three themes for his work: the studio, the museum, and the street. His Poverty Series, for example, works with photographs of people on the street. His Splash donation is a riff on the studio theme, with photographs taken of his workspace in Paris, in February of 2010. “I always stay in the same room in Paris, in the Hotel de Nice, right in the Marais area,” says Wallace. “It’s lovely. It’s my home away from home.”

That winter, Wallace worked on the Hotel Series. He photographed sketches at his table at the hotel and printed them at a nearby shop. He treats them as references for his inkjet studies, the larger works displayed at galleries. Before he could get to that point, however, he and his wife switched apartments. They needed more space to be able to invite friends to stay. So they moved to a new place in Les Halles, right across from the firehall on Rue du Jour. He re-photographed his drawings at another table – “you can see the sapeur pompiers just outside the window,” he says to me, pointing at the images – and completed the series. “I took the four monochromes: the blue, the yellow… and mapped the image of the Rue du Jour ones on top. So what it is, it’s a real mise en abyme, in other words, pictures within pictures.”

I took the four monochromes: the blue, the yellow… and mapped the image of the Rue du Jour ones on top. So what it is, it’s a real mise en abyme, in other words, pictures within pictures.

When he travels, Wallace only brings the necessities: a small portfolio, a set of coloured pencils, his camera, and a set of cutting tools and glue. He doesn’t have access to his shippers, printers or framers while he’s abroad, so he works on smaller pieces. “The work is very simple to do, and when the photographs are printed, they’re printed in the photo machines that anybody can use,” he says. “I try to keep everything as simple and straightforward as possible.”

Wallace travels regularly. He’s lived in London, and he’s lived in Paris twice for two-year stretches. He’s also spent a lot of time in Valencia where he has a permanent residency at the university. While he often takes his work with him, he does enjoy travel for the opportunity to be somewhere else and explore another culture. He’s bookish, a pure academic who loves to learn, analyze, and write.

I have library cards for all the major libraries and do a lot of research on French avant-garde poetry and the visual art of the turn of the century.

“I have library cards for all the major libraries and do a lot of research on French avant-garde poetry and the visual art of the turn of the century,” he tells me. His library at the studio is a testament to that. Before I leave he insists on passing a couple of books on to me. As a bookish person myself, I agree.

Wallace prefers going to an art exhibition than to the movies. “In a movie, you’re trapped in your seat and you’re two abstract suspended eyeballs kind of absorbed in the screen. When you’re watching a movie, you want to forget your body because you’re totally connected. I prefer an art exhibition because then your attentiveness is totally different. You’re tied to your body, you’re wandering, you’re moving around, you’re physically there in the context of a work of art, and often you’re with company, which is more interesting.”

An artist, a writer, a researcher, Wallace is also a musician. He was a member of the U-J3RK5s, a 70s punk band, with artists Jeff Wall and Rodney Graham, as well as artist and CBC radio host David Wisdom, among others. He played bass. He still does. And the drums, let’s not forget the drums in the room.

Forever the student.

MORE SPLASH ARTIST PROFILES

Jamie Evrard on Italy, Pretty Art, and the Circus

Bobbie Burgers on Building Stamina, Orchards, and Raising an Artistic Family

Lisa & Terrence Turner on Changing Careers, Making Mistakes, and Christmas Gifts

Andy Dixon on Punk Influence, New York City, and Becoming an Insider

Tiko Kerr on Halo, Creativity as Resource, and Resilience

Ed Spence on Tiny Squares, Transhumanism, and Diving into the Deep End