There’s no ceiling. And it’s the best of the best. That’s the thing about a city that’s so expensive to live in, the standards are so high and you can’t screw around out there. You have to be really good at what you do.

From punk kid to punk musician touring the world. From swag designer to visual artist and cultural commentator. Andy Dixon has become an art insider. How? It didn’t happen overnight, but it does have something to do with doing what you’re passionate about.

Dixon grew up in North Vancouver, a child of the 80s immersed in the punk scene. At eight, he picked up a guitar and started to play. By 12, he was playing in his first band: d.b.s. They made an unexpected entrance onto the world stage, riding on the tails of increasingly popular bands like Rancid, Green Day, NOFX, and Black Flag. Punk was seeing an international upswing, elevated by a core mantra of disestablishment and anarchy, and an unwillingness to sell out.

“Looking back I don’t know if we were very good or if it was more that we were seen as a gimmick because we were so young,” Dixon admits. “I didn’t see it that at the time, I just thought we were good.”

From a potentially burgeoning music career, how and why did Dixon pivot into the art world?

“The band I was in started getting bigger and bigger,” Dixon says. “I was the one elected to do t-shirt illustrations because from as far back as I can remember, I enjoyed drawing and making visual art of all kinds. I was accidentally sharpening my skills in ways I couldn’t have even planned for, really. Eventually, I realized it was taking off better than my music ever did and I just enjoyed doing it more.”

I was the one elected to do t-shirt illustrations because from as far back as I can remember, I enjoyed drawing and making visual art of all kinds. I was accidentally sharpening my skills in ways I couldn’t have even planned for, really.

Without a traditional educational background in art, Dixon’s style emerged from the bold and rough-around-the-edges style of 90s and early 2000s punk: hand-drawn lettering, subversion of cultural norms, illustrating metaphor, it was all part of Dixon’s artistic vernacular. “We caught some weird waves and then I got into some more experimental stuff, sound design and video work,” he says. Making the jump from musician to artist, however, wasn’t immediate. First, he was designing for his own band. Those works caught the eye of other bands and the punk community.

“The music community and the arts community, there’s a lot of overlap. Friends started an art collective and we put on a group show somewhere and someone from another gallery saw my piece and asked me to do a solo show, and that underground DIY gallery owned by some punk kids turned into this thing and this thing and this thing. It took its own course.”

Over the years, Dixon noticed two things: first, that he enjoyed making art more than making music; and second, that he wasn’t really a performer. “I don’t like being on stage and doing a thing with my body in front of people. That’s one thing that I love about visual arts. At openings, the work is done, it’s more of a celebration of work that’s done. I can do my work in solitude and it’s not really about my body performing for somebody.”

In a post-internet world, most of the images I’m playing with are just from Google searches. Then again, why would I have searched them if I hadn’t traveled? I’m not sure how to quantify how experience shapes an artist.

Creating art behind the scenes naturally evolved into bigger experimentation and the music world provided Dixon with plenty of inspiration.

“It’s hard to say what experiences change someone as an artist. I mean every experience changes someone as an artist, I guess — everything that one sees, eats, smells, or hears, gets filed away into some sort of artist database in my brain.”

Consider travel, for example. Dixon has traveled a lot in the past 20 years, but he’s not sure what role it’s played in his artistic voice. “Naturally, hanging out in Paris for a while will change it in some ways,” says Dixon, “But in a post-internet world, most of the images I’m playing with are just from Google searches. Then again, why would I have searched them if I hadn’t traveled? I’m not sure how to quantify how experience shapes an artist.”

There’s no ceiling. And it’s the best of the best. That’s the thing about a city that’s so expensive to live in, the standards are so high and you can’t screw around out there. You have to be really good at what you do. It’s inspiring to be around people doing the best.

There’s also a marked difference between travelling for leisure and travelling for work. “I’ve been to Paris like four times without ever seeing any of it,” Dixon explains of travelling with a band. “You’re late for the show and you go to the club which is on the outskirts of town anyways, and the sound guy’s late and you’re hanging out in this bar that looks just like the bar in Madrid. And the club has black-painted walls and smells like cigarettes. And then you go to the hotel and then you leave. So, I’ve kind of been everywhere and nowhere at the same time.”

And yet Dixon advocates travelling and experiencing new places. He recently spent a year in New York City and plans to take a few months in Los Angeles in late 2017. Despite delays with visas and planning a move, the thrill of a new city seems to excite him.

Of New York, he says, “I was working on a show there, so I decided instead of doing what I usually do — work on the show from my Vancouver studio and then shipping it — I would just do the work there. And that just sort of led to staying longer and longer. I have lots of friends there, [so] it was pretty easy to ingratiate into the world down there.”

“There’s no ceiling. And it’s the best of the best. That’s the thing about a city that’s so expensive to live in, the standards are so high and you can’t screw around out there. You have to be really good at what you do.”

Dixon explains why Vancouver is “a great place for the arts.” He sees two sides to its size: “In one way, it creates a tighter community, where people are maybe more apt to boost each other up. When I got back from New York, I liked the feeling of coming back and going to my local coffee shop and knowing everybody in there. And I went to Stan at Rath’s for my art supplies on Main Street — he makes all my stretchers. There’s this really nice feeling of community here. But the downside to having such a small city is that the ceiling is so low. Resources are scarce. There are only so many galleries, so many buyers, so many walls to paint, so many venues.”

When I got back from New York, I liked the feeling of coming back and going to my local coffee shop and knowing everybody in there. And I went to Stan at Rath’s for my art supplies on Main Street — he makes all my stretchers. There’s this really nice feeling of community here.

It really depends on what you’re looking for in your practice. I ask Dixon what he thinks of the globalization of the art market and the prevalence of social media. Does physical location still matter? “One of the key things to get exposure in a city like New York is to go there,” says Dixon. “Part of getting your work out there is getting you out there. Connections will be easier when you’re there.”

Despite that, Dixon is active on social media. His profiles evoke a mood, an opinion. His palette of bold pastels is one that’s particularly popular right now. His paintings and the glimpses into his life strike a chord, even when they don’t represent the sheer scale of his work.

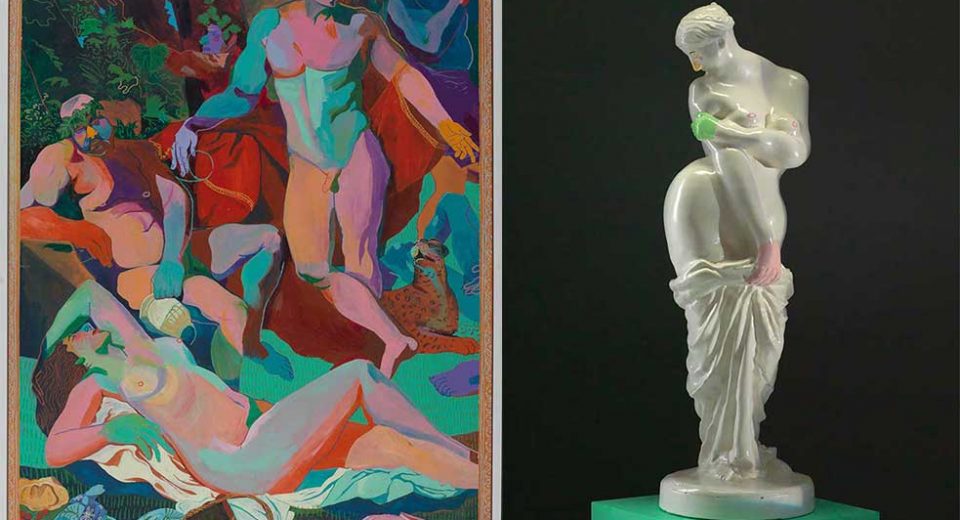

Dixon regularly searches online for luxury items. “There are many dimensions to it,” he tells me. “One is that I grew up in a punk scene; in the 90s there was a lot of dogmatic code about not selling out and being true. I’m playing a bit with that: a bit of a self-deprecating joke on what it means to sell out versus just being successful. I think, as a punk kid who’s lived under the poverty line for 18 years, I started to see the irony of making these works for prices I couldn’t even afford myself, and they become these sort of luxury items in themselves. I’m trying to show some self-awareness of the whole thing: my participation in this scene, especially as an outsider because I didn’t go to art school and, frankly, I don’t know what I’m doing, I’m able to play with things a bit more because of that.”

In the 90s there was a lot of dogmatic code about not selling out and being true. I’m playing a bit with that: a bit of a self-deprecating joke on what it means to sell out versus just being successful.

And yet, you can’t really call Andy Dixon an outsider to the art world. At least not anymore. With over six years of fine art painting under his belt, he’s at the very least a rising star. He’s exhibited internationally and recently released a printed collection of his works, Luxury Object. “It’s funny when that happens,” Dixon says. “That you can only be an “outsider” artist for so long and then you’re just not anymore, because you’re just in it.”

In Vancouver, where Dixon still spends most of his time and has a network of friends and advocates, his practice is flourishing. This year, he participated in the Vancouver Mural Festival. It’s his first mural, a sprawling 92 by 72 foot wall visible from East 4th between Quebec and Main.

“The approach was to align myself with people who know what they’re doing,” Dixon tells me. “I had no idea what it would take. The mural fest put me in touch with someone who was a friend of mine anyways, Scott Sueme, and we had a little chat to figure out the logistics. Between me knowing how my paintings are normally done and his expertise in knowing how a mural is done, we combined those processes together and came up with this unique [way] of how to get it done.”

It’s something I remember from when I was eight years old and drawing my first Garfield: I just started in a spot with one eye and then here’s his next eye.

Dixon painted it first on canvas (at scale) before printing it and projecting the image onto the massive brick wall. His team plotted anchor points and spray-painted key lines before just going at it. Overall, it took them eight days. The painting also showed and sold at Art Seattle just a week prior to the Mural Festival.

Dixon donated two items courtesy of Winsor Gallery and sold as one auction item for Splash 2017. He wanted to donate, he says, because he’s influenced by children’s work. “One of the main things I do in my studio, actually, is I try to remember what it’s like to be a child and make visual art in a way that maybe gets lost as you get older. I don’t sketch out my work, for example. It’s something I remember from when I was eight years old and drawing my first Garfield: I just started in a spot with one eye and then here’s his next eye. So I don’t map out my pieces at all, I just start in one spot and work my way out. The way I paint and apply my line work I owe a lot to the way that children see the world.”

MORE SPLASH ARTIST PROFILES

Tiko Kerr on Halo, Creativity as Resource, and Resilience

Ed Spence on Tiny Squares, Transhumanism, and Diving into the Deep End

Hank Bull on Artist-Run Centres, Collaboration, and Boxes

Ian Wallace on Photography, Expo 86, and the Image in an Image

Jamie Evrard on Italy, Pretty Art, and the Circus

Bobbie Burgers on Building Stamina, Orchards, and Raising an Artistic Family

Lisa and Terrence Turner on Changing Careers, Making Mistakes, and Christmas Gifts